Rudy Van Gelder died.

This man seems immortal with such a contribution to this genre and studio recording. His immense recording catalogue is unreal. So cool to browse through these sessions (turning into albums) and line-ups.

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/26/a...jazz-on-record-dies-at-91.html?mwrsm=Facebook

Rudy Van Gelder, an audio engineer whose work with

Miles Davis,

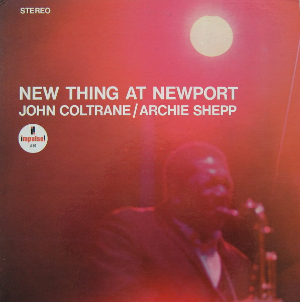

John Coltrane and numerous other musicians helped define the sound of jazz on record, died on Thursday at his home, which doubled as his studio, in Englewood Cliffs, N.J. He was 91.

His death was confirmed by his assistant, Maureen Sickler.

Mr. Van Gelder, as he took pains to explain to interviewers, was an engineer and not a producer. He was not in charge of the sessions he recorded; he did not hire the musicians or play any role in choosing the repertoire. But he had the final say in what the records sounded like, and he was, in the view of countless producers, musicians and listeners, better at that than anyone.

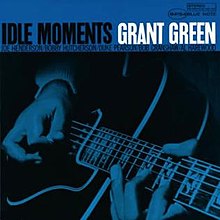

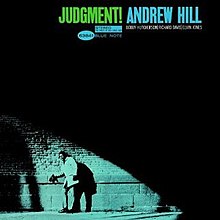

The many albums he engineered for Blue Note, Prestige, Impulse and other labels in the 1950s and ’60s included acknowledged classics like Coltrane’s “A Love Supreme,” Davis’s “Walkin’,” Herbie Hancock’s “Maiden Voyage,” Sonny Rollins’s “Saxophone Colossus” and Horace Silver’s “Song for My Father.”

In the 1970s he worked primarily for CTI Records, the most commercially successful jazz label of the period, where his discography included hit albums like Esther Phillips’s “What a Diff’rence a Day Makes” and Grover Washington Jr.’s “Mister Magic.”

“I think I’ve been associated with more records, technically, than anybody else in the history of the record business,” Mr. Van Gelder told The New York Times in 1988.

Mr. Van Gelder was reluctant to reveal too many specifics about his recording techniques. But he was clear about his goal: He wanted, he told Marc Myers of the website

JazzWax in 2012, “to get electronics to accurately capture the human spirit,” and to make the records he engineered sound “as warm and as realistic as possible.”

Comparing Mr. Van Gelder’s approach to that of other engineers in the journal Current Musicology in 2001, Dan Skea observed, “Whereas earlier jazz recordings seemed to come at the listener from a distance, Van Gelder found ways to approach and capture the music at closer range, and to more clearly convey jazz’s characteristic sense of immediacy.”

Mr. Van Gelder himself put it this way: “When people talk about my albums, they often say the music has ‘space.’ I tried to reproduce a sense of space in the overall sound picture.”

He added: “I used specific microphones located in places that allowed the musicians to sound as though they were playing from different locations in the room, which in reality they were. This created a sensation of dimension and depth.”

He also prided himself on being at the cutting edge of recording technology. He was one of the first engineers in the United States to use the state-of-the-art microphones made by the German company Neumann (because, he said, a Neumann “could capture sounds that other microphones couldn’t”). He was early to embrace magnetic recording tape and then digital recording.

Rudolph Van Gelder was born in Jersey City on Nov. 2, 1924. His parents, Louis Van Gelder and the former Sarah Cohen, ran a women’s clothing store in Passaic, N.J.

He became interested in jazz at an early age — he played trumpet, although by his own account not well — while developing a parallel passion for sound technology. When he was 12 he acquired a home recording device that included a turntable and discs. In high school he became a ham radio operator.

But he did not originally think he could make a living as a recording engineer, and attended the Pennsylvania College of Optometry in Philadelphia. “I felt that studying optometry would give me the mental discipline I needed and a steady income after I graduated,” he later recalled.

For more than a decade he was an optometrist by day and a recording engineer in his spare time.

He originally worked out of a studio in his parents’ living room in Hackensack, N.J. Not until 1959 — by which time he had already engineered some of the most celebrated recordings in jazz history — could he afford to make engineering his full-time occupation, shifting his base of operations to an elaborate home studio that he designed himself in Englewood Cliffs.

“I never made much money while practicing optometry after college,” he said in the JazzWax interview. “I made more from making records. But everything I made as an optometrist went into new recording equipment and, eventually, into building my studio in Englewood Cliffs from the ground up.”

In 1952, after he had been recording 78-r.p.m. discs of local musicians and singers for several years, he attracted the attention of Alfred Lion of

Blue Note Records, the leading jazz label of the day. Mr. Lion began using him regularly, and other record companies quickly followed suit.

Mr. Van Gelder was known not just for his skill as an engineer but also for his fastidiousness, as exemplified by his insistence on wearing gloves while working. “I was the guy doing everything — setting up the chairs, running the floor cables, setting the microphones, working the console,” he explained in 2012. “I didn’t want to handle all of my fine, expensive equipment with dirty hands.”

Unlike many audio engineers, Mr. Van Gelder was involved in every aspect of making records, from preparation to mastering, the final stage in the process, in which the music on tape was transferred to disc for record-plant pressing. “I always wanted to be in control of the entire recording chain,” he said. “Why not? It had my name on it.”

In 1999 he began remastering many of his Blue Note sessions for CD; the results were released to much fanfare as the Rudy Van Gelder Editions. He later did the same for his Prestige and CTI recordings.

Mr. Van Gelder was married twice; both marriages ended with his wives’ deaths. He is survived by a brother, Leon.

He was named a National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Master in 2009 and received lifetime achievement awards from the Recording Academy in 2012 and the Audio Engineering Society in 2013.

When he learned that he would be honored by the N.E.A. at a ceremony in New York, Mr. Van Gelder said in a statement, “I thought of all the great jazz musicians I’ve recorded through the years, how lucky I’ve been that the producers I worked with had enough faith in me to bring those musicians to me to record.”

And then, he added, “I thought, ‘I’ll have to get a suit.’”