You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

European Politics

- Thread starter Forostar

- Start date

Re: European Union

I have heard it is mostly because of pollution from the Baltic States, Poland, and St Petersburg. Is there any truth to that?

I have heard it is mostly because of pollution from the Baltic States, Poland, and St Petersburg. Is there any truth to that?

Forostar

Ancient Mariner

Re: European Union

OK. Just read a bit more about it. St Petersburg is the biggest city in the Baltic Sea region and the biggest single point source of pollution via the Neva, the biggest river in the region.

Probably the main sources to pollution are river flows, factories and spill water from vessels.

By the way: I swam in the Baltic Sea in 2002, near Sopot and Hel.

The beach was crowded.

OK. Just read a bit more about it. St Petersburg is the biggest city in the Baltic Sea region and the biggest single point source of pollution via the Neva, the biggest river in the region.

Probably the main sources to pollution are river flows, factories and spill water from vessels.

By the way: I swam in the Baltic Sea in 2002, near Sopot and Hel.

The beach was crowded.

Invader

Ancient Mariner

Re: European Union

What you don't hear about is the contribution of Finnish agriculture. Even though Finnish farmers get subsidies from the EU for farming "clean" and not letting fertilizers etc. get into the rivers, many don't really use the subsidies to achieve this goal. They get away with this because the centre party (now in government, facing accusations of corruption in election fundings) has its support in the countryside and farmers, and conveniently turn a blind eye.

I don't know what the water is like in Poland, Foro, but it's ok to swim for most part of the year. Here, though, it gets bad for the health around July most years, because a type of algae called "sinilevä" spreads in the warmer water and it can cause some poisoning especially in smaller children (not very severe though). It looks like this, though usually doesn't get that bad close to the shore:

Maybe that doesn't occur down south, though; the Baltic Sea is pretty big.

What you don't hear about is the contribution of Finnish agriculture. Even though Finnish farmers get subsidies from the EU for farming "clean" and not letting fertilizers etc. get into the rivers, many don't really use the subsidies to achieve this goal. They get away with this because the centre party (now in government, facing accusations of corruption in election fundings) has its support in the countryside and farmers, and conveniently turn a blind eye.

I don't know what the water is like in Poland, Foro, but it's ok to swim for most part of the year. Here, though, it gets bad for the health around July most years, because a type of algae called "sinilevä" spreads in the warmer water and it can cause some poisoning especially in smaller children (not very severe though). It looks like this, though usually doesn't get that bad close to the shore:

Maybe that doesn't occur down south, though; the Baltic Sea is pretty big.

Forostar

Ancient Mariner

Re: European Union

That indeed looks like shit, Invader. Maybe it's also worse in Poland now. I was there 7 years ago.

Here another good thing about the EU:

One for all, all for one.

That indeed looks like shit, Invader. Maybe it's also worse in Poland now. I was there 7 years ago.

Here another good thing about the EU:

One for all, all for one.

Forostar

Ancient Mariner

Re: European Union

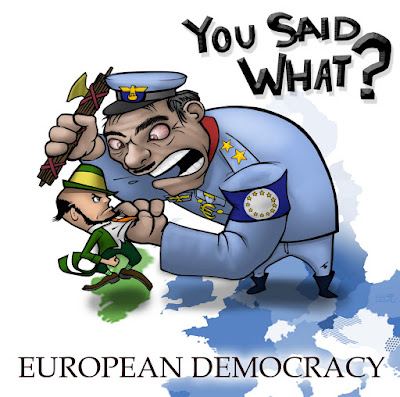

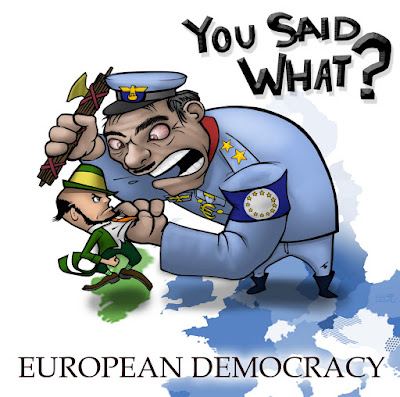

Seems like there's a terrible anti-European Union campaign going on in Ireland. Europe has actually invested a lot in Ireland over the years. Now Ireland needs Europe because they are close to bankrupt. What do many of them say against the upcoming treaty? "NO! Europe kills our babies (abortion) and oldies (euthanasia)."

These matters are not in the Lisbon treaty, but the campaign is so dirty and people actually believe all this shit.

Q&A: Ireland's new Lisbon vote

The Republic of Ireland will hold a second referendum on the EU's Lisbon Treaty on 2 October - a vote that could be make-or-break for the treaty.

Irish voters rejected the treaty in a referendum on 13 June 2008, with 53.4% voting "No" and 46.6% "Yes".

EU governments responded with legally binding "guarantees" to try to convince Irish voters that Lisbon would not weaken Irish sovereignty in certain key areas.

The Irish have already rejected the treaty - so why is another referendum being held?

The Irish government strongly backs the treaty, and is intent on signing it into Irish law. But Ireland is legally obliged to put it to a referendum first. In 1987 its Supreme Court ruled that any major amendment to an EU treaty entails an amendment to the Irish constitution - and that requires a referendum.

EU governments see the treaty as fundamental to the 27-nation bloc's future success. Without it, they argue, the EU's decision-making processes will remain slow and cumbersome, because they date back to when the EU consisted of only 15 nations.

After a decade of difficult negotiations many EU leaders are loath to see the treaty scuppered because of Ireland. They say there is no "Plan B" to refashion the treaty if it is rejected again.

The treaty's opponents insist that "No means No" - that the democratic will of Irish voters must be respected, and that this second referendum is just a device for the EU to force the treaty through.

Why is this referendum so important?

The treaty can only take effect if all the EU member states ratify it - and nearly all of the others have done so.

Ireland is the only EU member state to put the Lisbon Treaty to a referendum, so this vote is seen as a major hurdle. If the Irish vote "Yes" then the treaty could take effect in the coming months.

Apart from Ireland, could anything else stop the treaty?

Yes. A question mark still hangs over treaty ratification. Czech anti-Lisbon senators plan to file a second complaint against the treaty in the country's constitutional court on 29 September - and that could further delay ratification.

The court rejected an earlier complaint, ruling that the treaty was compatible with the Czech constitution.

The Eurosceptic Czech President, Vaclav Klaus, could delay signing the treaty until the outcome of the new court case - and there is speculation that this could play into the hands of the British Conservatives.

The Conservatives have promised to call a British referendum on Lisbon if they win the UK general election next April or May and if the treaty is not fully ratified by then.

In Poland, President Lech Kaczynski says he will not sign the treaty until the Irish voters give their verdict.

Despite pressure for referendums to be held in several EU states, governments have resisted. They argue that Lisbon merely amends earlier treaties, so there is no need for a referendum.

What if the Irish reject the treaty again?

A "No" vote would plunge the EU into a crisis - probably one of the most serious in its history.

It would damage the EU's credibility internationally and among European voters. It would probably scupper the treaty, though the countries that have ratified it might still manage to cherry-pick parts of it and introduce some of the institutional changes anyway.

It would certainly delay, at the very least, the institutional reforms that EU leaders say are long overdue. French and Dutch voters rejected the EU constitution back in 2005 - and European leaders are very reluctant to enter into another prolonged debate.

The number of EU commissioners would have to be cut, because the existing Nice Treaty says so. Under Lisbon, the number would remain at 27.

Further EU enlargement would be put on hold, as France and Germany say it cannot happen unless Lisbon is in force.

In the long term, it could lead to a "two-speed" Europe, with the more pro-integration countries forming an "inner core".

What has changed since the last Irish referendum?

Ireland's economy has been hit hard by the global credit crunch, which began a year ago. The days of the "Celtic Tiger" are certainly over - and that may persuade some that Europe's help is needed.

Economic insecurity is expected to be a big factor in the referendum this time - and pro-Lisbon campaigners have wasted no time in reminding voters of Ireland's traditional position as a "good European".

Opinion polls point to a majority "Yes" vote, but last time the "Yes" camp was leading in opinion polls too, so the Irish government knows there is no room for complacency. Polls also suggest that the government is unpopular, so it has a fight on its hands.

The leader of the anti-Lisbon campaign group Libertas, businessman Declan Ganley, played a major role last time and he has rejoined the "No" campaign. But he suffered a big blow in the June European elections, when Libertas failed to win a seat.

The "Yes" campaign appears to be better funded than last time. It has had big donations from the computer firm Intel and budget airline Ryanair.

The Irish government has secured legally binding EU "guarantees" that Lisbon will not affect Irish sovereignty over some key issues raised by voters. The guarantees - yet to be attached to the treaty - cover Irish neutrality, taxation and "family" issues such as abortion. Dublin had told its EU partners that there could be no second referendum without these guarantees.

The EU has also promised that Ireland will keep its EU commissioner - another issue that had worried Irish voters.

"No" campaigners say these promises are worthless because they are not written into the treaty itself.

Who is in the "Yes" camp?

All the main political parties apart from Sinn Fein, namely: the governing Fianna Fail and their allies the Greens, Fine Gael (the main opposition party) and the Labour Party.

Most of the industry and business associations and trade unions also support the treaty.

There are also pro-Lisbon citizens' groups, including Ireland for Europe, Women for Europe and Generation Yes - which is especially targeting young voters.

Who is in the "No" camp?

Sinn Fein - the only "No" party in parliament - and the lone MEP of the Socialist Party, Joe Higgins.

Declan Ganley, who made such an impact last time.

There is also a "No" alliance of 135 councillors, and the second largest union in Ireland, Unite.

There is the lobby group "Farmers for No" and various citizens' groups, including Coir and the People Before Profit Alliance.

If the treaty is fully ratified how will it change the EU?

A politician will be chosen as president of the European Council - the grouping of EU governments - for two-and-a-half years. The idea is to make policy more consistent over a longer period. Under the current system countries take turns at being president for six months.

A new foreign policy post will combine the jobs of the existing foreign affairs supremo Javier Solana and the external affairs commissioner, Benita Ferrero-Waldner, to give the EU more clout on the world stage.

There will be a redistribution of voting weights between the member states, phased in between 2014 and 2017. Qualified majority voting (QMV) will be based on a "double majority" of 55% of member states, accounting for 65% of the EU's population.

QMV will spread to new policy areas and the European Parliament will have a bigger say over justice and home affairs, including immigration. So MEPs' powers of "co-decision" with the national governments will increase. Individual states will retain the power to veto legislation in the areas of tax, foreign policy, defence and social security.

Most of these changes echo those in the defunct EU constitution - a fact acknowledged by many European leaders.

Seems like there's a terrible anti-European Union campaign going on in Ireland. Europe has actually invested a lot in Ireland over the years. Now Ireland needs Europe because they are close to bankrupt. What do many of them say against the upcoming treaty? "NO! Europe kills our babies (abortion) and oldies (euthanasia)."

These matters are not in the Lisbon treaty, but the campaign is so dirty and people actually believe all this shit.

Q&A: Ireland's new Lisbon vote

The Republic of Ireland will hold a second referendum on the EU's Lisbon Treaty on 2 October - a vote that could be make-or-break for the treaty.

Irish voters rejected the treaty in a referendum on 13 June 2008, with 53.4% voting "No" and 46.6% "Yes".

EU governments responded with legally binding "guarantees" to try to convince Irish voters that Lisbon would not weaken Irish sovereignty in certain key areas.

The Irish have already rejected the treaty - so why is another referendum being held?

The Irish government strongly backs the treaty, and is intent on signing it into Irish law. But Ireland is legally obliged to put it to a referendum first. In 1987 its Supreme Court ruled that any major amendment to an EU treaty entails an amendment to the Irish constitution - and that requires a referendum.

EU governments see the treaty as fundamental to the 27-nation bloc's future success. Without it, they argue, the EU's decision-making processes will remain slow and cumbersome, because they date back to when the EU consisted of only 15 nations.

After a decade of difficult negotiations many EU leaders are loath to see the treaty scuppered because of Ireland. They say there is no "Plan B" to refashion the treaty if it is rejected again.

The treaty's opponents insist that "No means No" - that the democratic will of Irish voters must be respected, and that this second referendum is just a device for the EU to force the treaty through.

Why is this referendum so important?

The treaty can only take effect if all the EU member states ratify it - and nearly all of the others have done so.

Ireland is the only EU member state to put the Lisbon Treaty to a referendum, so this vote is seen as a major hurdle. If the Irish vote "Yes" then the treaty could take effect in the coming months.

Apart from Ireland, could anything else stop the treaty?

Yes. A question mark still hangs over treaty ratification. Czech anti-Lisbon senators plan to file a second complaint against the treaty in the country's constitutional court on 29 September - and that could further delay ratification.

The court rejected an earlier complaint, ruling that the treaty was compatible with the Czech constitution.

The Eurosceptic Czech President, Vaclav Klaus, could delay signing the treaty until the outcome of the new court case - and there is speculation that this could play into the hands of the British Conservatives.

The Conservatives have promised to call a British referendum on Lisbon if they win the UK general election next April or May and if the treaty is not fully ratified by then.

In Poland, President Lech Kaczynski says he will not sign the treaty until the Irish voters give their verdict.

Despite pressure for referendums to be held in several EU states, governments have resisted. They argue that Lisbon merely amends earlier treaties, so there is no need for a referendum.

What if the Irish reject the treaty again?

A "No" vote would plunge the EU into a crisis - probably one of the most serious in its history.

It would damage the EU's credibility internationally and among European voters. It would probably scupper the treaty, though the countries that have ratified it might still manage to cherry-pick parts of it and introduce some of the institutional changes anyway.

It would certainly delay, at the very least, the institutional reforms that EU leaders say are long overdue. French and Dutch voters rejected the EU constitution back in 2005 - and European leaders are very reluctant to enter into another prolonged debate.

The number of EU commissioners would have to be cut, because the existing Nice Treaty says so. Under Lisbon, the number would remain at 27.

Further EU enlargement would be put on hold, as France and Germany say it cannot happen unless Lisbon is in force.

In the long term, it could lead to a "two-speed" Europe, with the more pro-integration countries forming an "inner core".

What has changed since the last Irish referendum?

Ireland's economy has been hit hard by the global credit crunch, which began a year ago. The days of the "Celtic Tiger" are certainly over - and that may persuade some that Europe's help is needed.

Economic insecurity is expected to be a big factor in the referendum this time - and pro-Lisbon campaigners have wasted no time in reminding voters of Ireland's traditional position as a "good European".

Opinion polls point to a majority "Yes" vote, but last time the "Yes" camp was leading in opinion polls too, so the Irish government knows there is no room for complacency. Polls also suggest that the government is unpopular, so it has a fight on its hands.

The leader of the anti-Lisbon campaign group Libertas, businessman Declan Ganley, played a major role last time and he has rejoined the "No" campaign. But he suffered a big blow in the June European elections, when Libertas failed to win a seat.

The "Yes" campaign appears to be better funded than last time. It has had big donations from the computer firm Intel and budget airline Ryanair.

The Irish government has secured legally binding EU "guarantees" that Lisbon will not affect Irish sovereignty over some key issues raised by voters. The guarantees - yet to be attached to the treaty - cover Irish neutrality, taxation and "family" issues such as abortion. Dublin had told its EU partners that there could be no second referendum without these guarantees.

The EU has also promised that Ireland will keep its EU commissioner - another issue that had worried Irish voters.

"No" campaigners say these promises are worthless because they are not written into the treaty itself.

Who is in the "Yes" camp?

All the main political parties apart from Sinn Fein, namely: the governing Fianna Fail and their allies the Greens, Fine Gael (the main opposition party) and the Labour Party.

Most of the industry and business associations and trade unions also support the treaty.

There are also pro-Lisbon citizens' groups, including Ireland for Europe, Women for Europe and Generation Yes - which is especially targeting young voters.

Who is in the "No" camp?

Sinn Fein - the only "No" party in parliament - and the lone MEP of the Socialist Party, Joe Higgins.

Declan Ganley, who made such an impact last time.

There is also a "No" alliance of 135 councillors, and the second largest union in Ireland, Unite.

There is the lobby group "Farmers for No" and various citizens' groups, including Coir and the People Before Profit Alliance.

If the treaty is fully ratified how will it change the EU?

A politician will be chosen as president of the European Council - the grouping of EU governments - for two-and-a-half years. The idea is to make policy more consistent over a longer period. Under the current system countries take turns at being president for six months.

A new foreign policy post will combine the jobs of the existing foreign affairs supremo Javier Solana and the external affairs commissioner, Benita Ferrero-Waldner, to give the EU more clout on the world stage.

There will be a redistribution of voting weights between the member states, phased in between 2014 and 2017. Qualified majority voting (QMV) will be based on a "double majority" of 55% of member states, accounting for 65% of the EU's population.

QMV will spread to new policy areas and the European Parliament will have a bigger say over justice and home affairs, including immigration. So MEPs' powers of "co-decision" with the national governments will increase. Individual states will retain the power to veto legislation in the areas of tax, foreign policy, defence and social security.

Most of these changes echo those in the defunct EU constitution - a fact acknowledged by many European leaders.

Hunlord

Trooper

Re: European Union

I'll post more on this tomorrow or the next day when I have time, but the reason it was voted No last time, in my opinion, was because no information was given out by the Yes side about what the treaty actually meant, whereas this time, it seems a lot more balanced. Again. I'll talk more whenever.

And Onhell, you can't get an abortion over here, you'd have to travel outside the country, so I have no idea what you're on about.

I'll post more on this tomorrow or the next day when I have time, but the reason it was voted No last time, in my opinion, was because no information was given out by the Yes side about what the treaty actually meant, whereas this time, it seems a lot more balanced. Again. I'll talk more whenever.

And Onhell, you can't get an abortion over here, you'd have to travel outside the country, so I have no idea what you're on about.

Re: European Union

Although I hope the Irish will say "Yes" this time and I acknowledge that the result of the last referendum was both non-representative (with a turnout of just over 50%) and unfair towards all other European countries that toiled hard to create a treaty that is acceptable for all, I still can't get over this: The result of the last referendum was "No". So a second referendum will be held; it would not have been held if the answer would have been "Yes". I.e. it seems like the EU is not accepting a no for an answer and forces people to say "yes". I know that is not the case, but that is what it will appear like to many.

Although I hope the Irish will say "Yes" this time and I acknowledge that the result of the last referendum was both non-representative (with a turnout of just over 50%) and unfair towards all other European countries that toiled hard to create a treaty that is acceptable for all, I still can't get over this: The result of the last referendum was "No". So a second referendum will be held; it would not have been held if the answer would have been "Yes". I.e. it seems like the EU is not accepting a no for an answer and forces people to say "yes". I know that is not the case, but that is what it will appear like to many.

Forostar

Ancient Mariner

Re: European Union

In the Netherlands they also said "No" and we didn't have a second referendum. I am glad about it, since a lot of people only voted "No" because of anger which had nothing to do with the treaty.

Looks like Ireland will say yes. After this we still have Poland plus especially the Czech republic is doing difficult.

In the Netherlands they also said "No" and we didn't have a second referendum. I am glad about it, since a lot of people only voted "No" because of anger which had nothing to do with the treaty.

Looks like Ireland will say yes. After this we still have Poland plus especially the Czech republic is doing difficult.

Re: European Union

The way I see it is that the EU would have to alter the treaty in some way before asking for another referendum.

The way I see it is that the EU would have to alter the treaty in some way before asking for another referendum.

Forostar

Ancient Mariner

Re: European Union

Well well... Wilders won his case vs Britain (Home Office). Ban overturned.

Forostar said:Dutch Right-wing politician and controversial anti-Islam campaigner Geert Wilders has been refused entry to the United Kingdom despite being invited to visit by a member of the House of Lords, the British parliament's upper chamber.

Well well... Wilders won his case vs Britain (Home Office). Ban overturned.

Re: European Union

Good. I don't like what Wilders has to say, but he should be allowed to say it.

Good. I don't like what Wilders has to say, but he should be allowed to say it.

Re: European Union

We've had this discussion; I don't think hate speech should be a crime.

We've had this discussion; I don't think hate speech should be a crime.