You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Jazz?

- Thread starter Yax

- Start date

SixesAlltheway

Ancient Mariner

Forostar said:Just listened to "East", no_5, but I have to be honest and say that I'm not over the moon by this song.

For such length, I thought it lacked variation and the tone was constantly the same, and the soloing too.

And Martino lacked the spark to lift it to a higher level. Just my opinion of course, but hey, I am spoiled by certain other guitar players.

I'm listening to the title track right now and really digging it. The intro is pretty haunting with some great melodies and then they let it rip in the middle for sure!

More of these kinda recoomendations please

A Jazz artist I really appreciate and love the music of is Hugh Masekela, a composer, trumpeteer from South Africa. This song from his album Home is where the music is is really good I feel. Very rich and warm sound.

Click: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BwI6uJ2J-DM

____no5

Free Man

John Coltrane -Olé part I & part II (one song normally, 18 frenetic minutes of pure awesome...)

______no5 said:I will suggest you three albums for to start. The world of jazz as well as the world of blues, is full of collaborations

so if you buy these three albums, and then read the credits and make some research,

then you'll have at least other 10 albums at hand.

...

1) Krupa & Rich, 1956

2) Miles Davis -Kind of Blue, 1959

3) John Coltrane -Olé, 1961

Let’s see how it works the 3 albums theory.

A fellow Maidenfan, let’s say Yax, decides to follow my advice; he buys, the three albums recommended: Krupa & Rich, Kind of Blue & Ole. He plays Kind of Blue.

1. "So What" – 9:22

2. "Freddie Freeloader" – 9:46

3. "Blue in Green" – 5:37

4. "All Blues" – 11:33

5. "Flamenco Sketches" – 9:26

Though precise figures have been disputed, Kind of Blue has been cited by many music writers not only as Davis's best-selling album, but as the best-selling jazz record of all time. On October 7, 2008, it was certified quadruple platinum in sales by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA). It has been regarded by many critics as the greatest jazz album of all time and Davis's masterpiece. The album's influence on music, including jazz, rock and classical music, has led music writers to acknowledge it as one of the most influential albums of all time. In 2002, it was one of fifty recordings chosen that year by the Library of Congress to be added to the National Recording Registry. In 2003, the album was ranked number 12 on Rolling Stone magazine's list of the 500 greatest albums of all time.

After some listens, he’s fucking astonished and wants to discover more jazz, other than Davis. He checks the credits…

Miles Davis: trumpet

John Coltrane: tenor saxophone

Cannonball Adderley: alto saxophone

Paul Chambers: bass

Bill Evans: piano

Wynton Kelly: piano

Jimmy Cobb: drums.

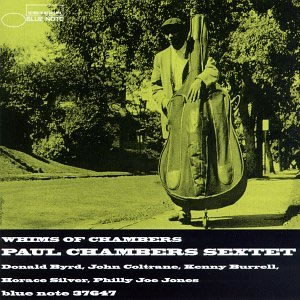

…and he picks Paul Chambers, partly out of lack, partly cause he’s a Maidenfan and Chambers is a bassist. He goes to his local record shop and searches something of him. He finds Whims of Chambers (1956), one of the most easy-to-be-found Chambers records:

1. "Omicron" (Donald Byrd) – 7:15

2. "Whims Of Chambers" – 4:03

3. "Nita" (John Coltrane) – 6:03

4. "We Six" (Byrd) – 7:39

5. "Dear Ann" – 4:18

6. "Tale Of The Fingers" – 4:41

7. "Just For The Love" (Coltrane) – 3:41

Of the seven songs on this Blue Note CD reissue, four are more common than the other three because they contain solos by tenor saxophonist John Coltrane and have therefore been reissued more often. Actually there are quite a few solos in the all-star sextet (which includes the bassist-leader, Coltrane, trumpeter Donald Byrd, guitarist Kenny Burrell, pianist Horace Silver and drummer Philly Joe Jones) and all of the players get their chances to shine on this fairly spontaneous hard bop set. Coltrane's two obscure compositions ("Nita" and "Just for the Love") are among the more memorable tunes and are worth reviving. "Tale of the Fingers" features the quintet without Coltrane, the rhythm section stretches out on "Whims of Chambers" and "Tale of the Fingers" is a showcase for Chambers bowed bass. This is a fine effort and would be worth picking up by straightahead jazz fans even if John Coltrane had not participated.

He loves the terrific sound of the double bass, the excellent guitar work of Kenny Burrell, Donald Byrd’s trumpet and worships Coltrane’s sax.

However, he decides to try except Coltrane, something with the drummer Philly Joe Jones, impressed by his solo in the title track.

He picks up Clark Terry’s In Orbit (1958) and Coltrane’s Giants Steps (1960)

1. "In Orbit" (Terry)

2. "One Foot in the Gutter (Terry)

3. "Trust in Me"

4. "Let's Cool One" (Monk)

5. "Pea-Eye" (Terry)

6. "Argentina" (Terry)

7. "Moonlight Fiesta" (Mills, Tizol)

8. "Buck's Business" (Terry)

9. "Very Near Blue" (Cassey)

10. "Flugelin' the Blues" (Terry)

In Orbit is going o be an apocalypse, as he’ll discover the genious of Thelonious Monk, inventor of bebop and one of the most important musician, ever. He marks this name, for the next time and he plays Giant Steps.

1. "Giant Steps" – 4:43

2. "Cousin Mary" – 5:45

3. "Countdown" – 2:21

4. "Spiral" – 5:56

5. "Syeeda's Song Flute" – 7:00

6. "Naima" – 4:21

7. "Mr. P.C." (Mr. Paul Chambers) – 6:57

Giant Steps was Coltrane’s second album to be recorded by the Atlantic label, and marked the first time that all of the pieces on a recording had been composed by him. The recording exemplifies Coltrane's melodic phrasing that came to be known as sheets of sound, and features the use of a new harmonic concept now referred to as Coltrane changes. Jazz musicians continue to use the "Giant Steps" chord progression, which consists of a peculiar set of chord progessions which often move in thirds, as a practice piece and as a gateway into modern jazz improvisation. The ability to play over the "Giant Steps"/Coltrane cycle remains to this day one of the benchmark standards by which a jazz musician's improvising skill is measured.

Yax, already charmed from the piano of Monk in the In Orbit, decides to take a chance also, for the pianist of Giant Steps, Tommy Flanagan. He goes again to the record shop and asks the record shop guy if he knows any worthy record with him on piano. The owner smiles and recommends him The Incredible Jazz Guitar of Wes Montgomery (1960) one of the most important jazz guitar records ever.

1. "Airegin" (Sonny Rollins) – 4:26

2. "D-Natural Blues" (Wes Montgomery) – 5:23

3. "Polka Dots and Moonbeams" (Burke, VanHeusen) – 4:44

4. "Four on Six" (Montgomery) – 6:15

5. "West Coast Blues" (Montgomery) – 7:26

6. "In Your Own Sweet Way" (Dave Brubeck) – 4:53

7. "Mr. Walker" (Montgomery) – 4:33

8. "Gone With the Wind" (Magidson, Wrubel) – 6:24

He also purchases Monk’s Brilliant Corners (1957):

1. "Brilliant Corners" – 7:42

2. "Ba-lue Bolivar Ba-lues-are" – 13:24

3. "Pannonica" – 8:50

4. "I Surrender Dear" (Harry Barris) – 5:25

5. "Bemsha Swing" (Thelonious Monk, Denzil Best) – 7:42

Brilliant Corners is a 1957 album by jazz musician Thelonious Monk. It was his third album for the Riverside label and the first, for this label, to include his own compositions. The complex title track required over a dozen takes in the studio, and is considered one of his most difficult compositions. In 2003, it was one of fifty recordings chosen that year by the Library of Congress to be added to the National Recording Registry.

Because of its historical significance the album was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1999.

He checks the credits and finds some names already met before, like Clark Terry & Paul Chambers. Nevertheless, his new discovery is now Max Roach. He notes his name for a next time

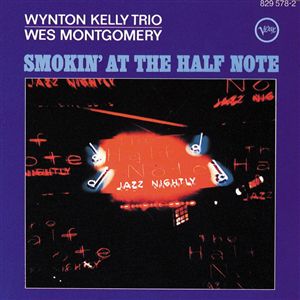

Yax, plays The Incredible Jazz Guitar of Wes Montgomery and rests speechless from the unique, created by his thumb, sound of Wes, so he decides to buy another record of the biggest jazz guitarist ever. He goes to the shop and checks the Montgomery records available. Smokin' at the Half Note attires his attention, by its credits:

Wes Montgomery – guitar

Wynton Kelly – piano

Paul Chambers – bass

Jimmy Cobb – drums

All of them, he has met before, in at least one of his only 8 jazz records. Eventually he buys it.

1. "No Blues" (Miles Davis)

2. "If You Could See Me Now"

3. "Unit 7" (Sam Jones)

4. "Four on Six"

5. "What's New"

Smokin' at the Half Note is essential listening for anyone who wants to hear why Montgomery's dynamic live shows were considered the pinnacle of his brilliant and incredibly influential guitar playing. Pat Metheny calls this "the absolute greatest jazz guitar album ever made," and with performances of this caliber ("Unit 7" boasts one of the greatest guitar solos ever recorded) his statement is easily validated. Montgomery never played with more drive and confidence, and he's supported every step of the way by a genuinely smokin' Wynton Kelly Trio.

Yax, decides now to take a chance with Wynton Kelly & the already noted Roach. Eventually he’ll get to know Dizzie Gilespie, Charles Mingus, Charlie Parker, Duke Ellington. And every new record will open him doors to a few other jazz records... It can go as far as he can handle. And the tale goes on and on and on!

Forostar

Ancient Mariner

Awesome man! Hats off! I like the way you keep injecting this topic. But there's no rush! Let's keep this alive as long as possible. I try to stick to once per week, to extend the life of this topic. But in the meantime, I certainly enjoy to read all this passionate promoting.

I came across those artists for sure, maybe via a different route, but still...

However, I haven't chosen to delve into Montgomery yet. Can't really say why, maybe subconciously because Montgomery was the great rival of Grant Green (my personal number one on guitar, and the most recorded musician of Blue Note). Also haven't heard a Clark Terry record yet, but I do know him from Brilliant Corners.

And welcome, join the club, SixesAlltheway! Sounds relaxed. Do you mind if I ask from what year it is? It helps me a bit to put jazz into context. Just like with films, I have this strange habit to increase my own curiosity when little trivia (such as a year, and/or musicians) are available.

I came across those artists for sure, maybe via a different route, but still...

However, I haven't chosen to delve into Montgomery yet. Can't really say why, maybe subconciously because Montgomery was the great rival of Grant Green (my personal number one on guitar, and the most recorded musician of Blue Note). Also haven't heard a Clark Terry record yet, but I do know him from Brilliant Corners.

And welcome, join the club, SixesAlltheway! Sounds relaxed. Do you mind if I ask from what year it is? It helps me a bit to put jazz into context. Just like with films, I have this strange habit to increase my own curiosity when little trivia (such as a year, and/or musicians) are available.

SixesAlltheway

Ancient Mariner

Forostar said:And welcome, join the club, SixesAlltheway! Sounds relaxed. Do you mind if I ask from what year it is? It helps me a bit to put jazz into context. Just like with films, I have this strange habit to increase my own curiosity when little trivia (such as a year, and/or musicians) are available.

Thanks! That particular song/album is from 1972. I have to say I've not really followed him that much, but he is still active and have released over 30 albums. But Home is where the music is is very recommendable, some great jazz tunes

____no5

Free Man

Charles Mingus, pt I

This post is a collage-text from various sites, plus some typing by yours truly. It goes from the early Mingus to the awesome 50s, my best Mignus era, though are 60s, which considered to be his golden years. In this first part you'll discovered the best jazz concert ever and one of my all time favorite songs, the mighty Haitian Fight Song. Bon courage for the reading and stay jazzy!

1922.

Born of Mingus in Arizona.

1940.

Charles Mingus starts playing in Lee Young’s group, admiring Ellington & Art Tatum.

Duke Ellington

1941-43.

He joins the Luis Armstrong band. He also plays with Kid Ory, Barney Bigard and Alvino Rey.

1945-48.

He works with the Russel Bros, Illinois Jacquet & Lionel Hampton band, for which he writes a few arrangements.

1950-51.

He moves in NY after a successful trio with Red Norvo & Tal Farlow. Things do not work well and he decides to work in a post office. Charlie Parker get him out of there. He plays with the Billy Taylor trio for a few months.

1952.

He launches a new record label (Debut) in partnership with Max Roach. The best known recording of the company issued (Jazz at Massey Hall, 1953), was of the most prominent figures in bebop. He starts to earn the respect of jazz world, but he’s an utter failure as a man. Difficult and unpredictable character, he is incapable to control his emotions. Sweetness, naivety and a need to be loved are lodged inside him together with hate, hostility and vulgarity. His psychological defects derive partly from his condition of being black with Red Indian blood: doubly an outsider.

1953.

This is the year of the historic concert at the Toronto Town Hall with Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell and Max Roach.

The Quintet -Jazz At Massey Hall, 1953

Jazz at Massey Hall is a renowned jazz album featuring a live performance by "The Quintet" on 15 May 1953 at Massey Hall in Toronto. The quintet was composed of some of the time's biggest names in jazz: Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Bud Powell, Charles Mingus, and Max Roach. It was the only time that the five men recorded together as a unit, and it was the last recorded meeting of Parker and Gillespie. Parker played a Grafton saxophone on this date; he could not be listed on the original album cover for contractual reasons, so was billed as "Charlie Chan" (an allusion to the fictional detective and to Parker's wife Chan). The record was originally issued on Mingus's label Debut, from a recording made by the Toronto New Jazz Society. Mingus took the recording to New York where he and Max Roach dubbed in the bass lines, which were under-recorded on most of the tunes, and exchanged Mingus soloing on "All the Things You Are."

The original plan was for the Jazz Society and the musicians to share the profits from the recording. However the audience was so small that the Society was unable to pay the musicians' fees. The musicians were all given NSF checks, and only Parker was able to actually cash his; Gillespie complained that he did not receive his fee "for years and years".

A 2004 re-issue contains the full concert, without the over-dubbing which was added by Charles Mingus on the original recording. The new version was titled "Complete Jazz at Massey Hall"

Jazz at Massey Hall was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1995. It is included in National Public Radio's "Basic Jazz Library". The concert was issued in some territories under the tag "the greatest jazz concert ever".

1. "Perdido" (Juan Tizol, Hans Lengfelder, Ervin M. Drake)

2. "Salt Peanuts" (Dizzy Gillespie, Kenny Clarke)

3. "All the Things You Are" (Jerome Kern, Oscar Hammerstein II)

4. "52nd Street Theme" (Thelonious Monk)

---

5. "Wee (Allen's Alley)" (Denzil Best)

6. "Hot House" (Tadd Dameron)

7. "A Night in Tunisia" (Gillespie, Frank Paparelli)

• Dizzy Gillespie — trumpet

• Charles Mingus — bass

• Charlie Parker — alto sax

• Bud Powell — piano

• Max Roach — drums

After the event, Mingus chose to overdub his barely-audible bass part back in New York; the original version was issued later. The two 10" albums of the Massey Hall concert (one featured the trio of Powell, Mingus and Roach) were among Debut Records' earliest releases. Mingus may have objected to the way the major record companies treated musicians, but Gillespie once commented that he did not receive any royalties "for years and years" for his Massey Hall appearance. The records though, are often regarded as among the finest live jazz recordings.

In the summer he founds the ‘Jazz Workshop’ gathering around him the cream of avant-garde music without making distinctions about the color of people’s skin: Teo Macero, John la Porta, Willie Denis, Eddie Bert, J.J. Johnson, kay Winding & Kenny Clarke. He begins to experiment with these people.

1955-56.

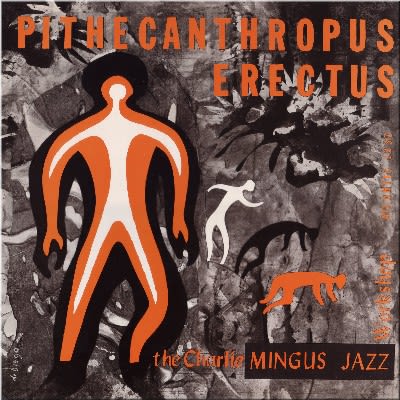

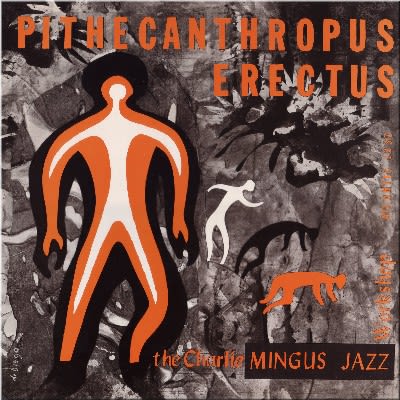

He plays with his group at the Café Bohemia in NY. Some genuine masterpieces as ‘Pithecanthropus erectus’ and ‘Haitian Fight Song’ come in light. In some of his songs social political meanings can be detected, condemning racial persecution and prejudice. Mingus’ arrangements are not fully composed, but just like Ellington, they have lots of space for the soloists to improvise.

Pithecanthropus erectus, 1955

1. "Pithecanthropus Erectus" – 10:36

2. "A Foggy Day" – 7:50 {George Gershwin}

3. "Profile of Jackie" – 3:11

4. "Love Chant" – 14:59

· Charles Mingus – Bass

· Jackie McLean – Alto Saxophone

· J. R. Monterose – Tenor Saxophone

· Mal Waldron – Piano

· Willie Jones – Drums

Pithecanthropus Erectus was Charles Mingus' breakthrough as a leader, the album where he established himself as a composer of boundless imagination and a fresh new voice that, despite his ambitiously modern concepts, was firmly grounded in jazz tradition. Mingus truly discovered himself after mastering the vocabularies of bop and swing, and with Pithecanthropus Erectus he began seeking new ways to increase the evocative power of the art form and challenge his musicians (who here include altoist Jackie McLean and pianist Mal Waldron) to work outside of convention. The title cut is one of his greatest masterpieces: a four-movement tone poem depicting man's evolution from pride and accomplishment to hubris and slavery and finally to ultimate destruction. The piece is held together by a haunting, repeated theme and broken up by frenetic, sound-effect-filled interludes that grow darker as man's spirit sinks lower. It can be a little hard to follow the story line, but the whole thing seethes with a brooding intensity that comes from the soloist's extraordinary focus on the mood, rather than simply flashing their chops. Mingus' playful side surfaces on "A Foggy Day (In San Francisco)," which crams numerous sound effects (all from actual instruments) into a highly visual portrait, complete with honking cars, ringing trolleys, sirens, police whistles, change clinking on the sidewalk, and more. This was the first album where Mingus tailored his arrangements to the personalities of his musicians, teaching the pieces by ear instead of writing everything out. Perhaps that's why Pithecanthropus Erectus resembles paintings in sound -- full of sumptuous tone colors learned through Duke Ellington, but also rich in sonic details that only could have come from an adventurous modernist. And Mingus plays with the sort of raw passion that comes with the first flush of mastery. Still one of his greatest.

[...]

Early 1955, Mingus is involved in a notorious incident while playing a club date billed as a "reunion" with Parker, Powell, and Roach. Powell, who suffered from alcoholism and mental illness (possibly exacerbated by a severe police beating and electroshock treatments), had to be helped from the stage, unable to play or speak coherently. As Powell's incapacitation became apparent, Parker stood in one spot at a microphone, chanting "Bud Powell...Bud Powell..." as if beseeching Powell's return. Allegedly, Parker continued this incantation for several minutes after Powell's departure, to his own amusement and Mingus' exasperation. Mingus took another microphone and announced to the crowd, "Ladies and gentlemen, please don't associate me with any of this. This is not jazz. These are sick people." This was Parker's last public performance; about a week later Parker died after years of substance abuse.

1957.

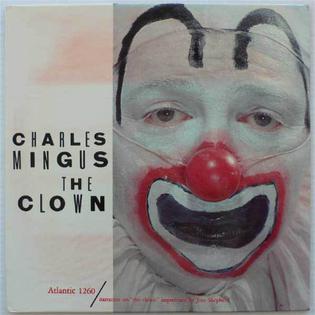

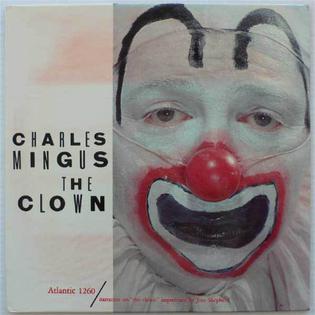

He contributes to the creation of the sound track for the film ‘Shadows’ by Cassavetes. Release of The Clown.

The Clown, 1957

1. "Haitian Fight Song" - 11:57

2. "Blue Cee" - 7:48

3. "Reincarnation of a Lovebird" - 8:31

4. "The Clown" - 12:29

The following excerpts come from the original liner notes and are statements made by Mingus himself.

On "Haitian Fight Song", Mingus said "[...] It has a folk spirit, the kind of folk music I've always heard anyway.[...] My solo in it it's a deeply concetrated one. I can't play it right unless I'm thinking about prejudice and persecution, and how unfair is it. There's sadness and cries in it, but also determination. And it usually ends with my feeling 'I told them! I hope somebody heard me!'".

"Blue Cee" is a standard blues in two keys, C and Bb, "but that's not noticeable and it ends up in C, basically", he said and continued "I heard some Basie in it and also some church-like feeling".

"Reincarnation of a Lovebird" is a composition dedicated to Bird. "I wouldn't say I set out to write a piece on Bird. [...] Suddenly I realize it was Bird. [...] In one way, the work isn't like him. It's built on long lines and most of his pieces were short lines. But it's my feeling about Bird. I felt like crying when I wrote it."

"The Clown" tells the story of a clown "who tried to please people like most jazz musicians do, but whom nobody liked until he was dead. My version of the story ended with his blowing his brains out with the people laughing and finally being pleased because they thought it was part of the act. I liked the way Jean changed the ending; leaves it more up to the listener."

1959.

This is a very creative year for Mingus, from the album ‘Mingus Ah Um’ with a homage to Charlie Parker (Bird Calls), Duke Ellington (Open Letter To Duke) and to Lester Young, who had recently died (Goodbye Pork Pie Hat). At the end of the 50s, Mingus is a famous personality, loved for his music and feared for his dissoluteness. The relations between him and his colleagues, journalists and producers are almost always turbulent. Sometimes, doing concerts, he urges on his musicians at the top of his voice, flattering them and insulting them, stopping numbers only to begin them again immediately afterwards, almost as if it was a rehearsal and not a payed performance. He takes absolutely no notice of the opinions of the critics and the audiences. This is something new and disconcerting, which creates his legendary image.

Mingus Ah Um, 1959

· "Better Git It in Your Soul" (7:23)

· "Goodbye Pork Pie Hat" (4:46/5:44)

· "Boogie Stop Shuffle" (3:41/5:02)

· "Self-Portrait in Three Colors" (3:10)

· "Open Letter to Duke" (4:56/5:51)

· "Bird Calls" (3:12/6:17)

· "Fables of Faubus" (8:13)

· "Pussy Cat Dues" (6:27/9:14)

· "Jelly Roll" (4:01/6:17)

Charles Mingus' debut for Columbia, Mingus Ah Um is a stunning summation of the bassist's talents and probably the best reference point for beginners. While there's also a strong case for The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady as his best work overall, it lacks Ah Um's immediate accessibility and brilliantly sculpted individual tunes. Mingus' compositions and arrangements were always extremely focused, assimilating individual spontaneity into a firm consistency of mood, and that approach reaches an ultra-tight zenith on Mingus Ah Um. The band includes longtime Mingus stalwarts already well versed in his music, like saxophonists John Handy, Shafi Hadi, and Booker Ervin; trombonists Jimmy Knepper and Willie Dennis; pianist Horace Parlan; and drummer Dannie Richmond. Their razor-sharp performances tie together what may well be Mingus' greatest, most emotionally varied set of compositions. At least three became instant classics, starting with the irrepressible spiritual exuberance of signature tune "Better Get It in Your Soul," taken in a hard-charging 6/8 and punctuated by joyous gospel shouts. "Goodbye Pork Pie Hat" is a slow, graceful elegy for Lester Young, who died not long before the sessions. The sharply contrasting "Fables of Faubus" is a savage mockery of segregationist Arkansas governor Orval Faubus, portrayed musically as a bumbling vaudeville clown (the scathing lyrics, censored by skittish executives, can be heard on Charles Mingus Presents Charles Mingus). The underrated "Boogie Stop Shuffle" is bursting with aggressive swing, and elsewhere there are tributes to Mingus' three most revered influences: "Open Letter to Duke" is a suite of three tunes; "Bird Calls" is inspired by Charlie Parker; and "Jelly Roll" is an idiosyncratic yet affectionate nod to jazz's first great composer, Jelly Roll Morton. It simply isn't possible to single out one Mingus album as definitive, but Mingus Ah Um comes the closest.

...to be continued...

This post is a collage-text from various sites, plus some typing by yours truly. It goes from the early Mingus to the awesome 50s, my best Mignus era, though are 60s, which considered to be his golden years. In this first part you'll discovered the best jazz concert ever and one of my all time favorite songs, the mighty Haitian Fight Song. Bon courage for the reading and stay jazzy!

1922.

Born of Mingus in Arizona.

1940.

Charles Mingus starts playing in Lee Young’s group, admiring Ellington & Art Tatum.

Duke Ellington

1941-43.

He joins the Luis Armstrong band. He also plays with Kid Ory, Barney Bigard and Alvino Rey.

1945-48.

He works with the Russel Bros, Illinois Jacquet & Lionel Hampton band, for which he writes a few arrangements.

1950-51.

He moves in NY after a successful trio with Red Norvo & Tal Farlow. Things do not work well and he decides to work in a post office. Charlie Parker get him out of there. He plays with the Billy Taylor trio for a few months.

1952.

He launches a new record label (Debut) in partnership with Max Roach. The best known recording of the company issued (Jazz at Massey Hall, 1953), was of the most prominent figures in bebop. He starts to earn the respect of jazz world, but he’s an utter failure as a man. Difficult and unpredictable character, he is incapable to control his emotions. Sweetness, naivety and a need to be loved are lodged inside him together with hate, hostility and vulgarity. His psychological defects derive partly from his condition of being black with Red Indian blood: doubly an outsider.

1953.

This is the year of the historic concert at the Toronto Town Hall with Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell and Max Roach.

The Quintet -Jazz At Massey Hall, 1953

Jazz at Massey Hall is a renowned jazz album featuring a live performance by "The Quintet" on 15 May 1953 at Massey Hall in Toronto. The quintet was composed of some of the time's biggest names in jazz: Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Bud Powell, Charles Mingus, and Max Roach. It was the only time that the five men recorded together as a unit, and it was the last recorded meeting of Parker and Gillespie. Parker played a Grafton saxophone on this date; he could not be listed on the original album cover for contractual reasons, so was billed as "Charlie Chan" (an allusion to the fictional detective and to Parker's wife Chan). The record was originally issued on Mingus's label Debut, from a recording made by the Toronto New Jazz Society. Mingus took the recording to New York where he and Max Roach dubbed in the bass lines, which were under-recorded on most of the tunes, and exchanged Mingus soloing on "All the Things You Are."

The original plan was for the Jazz Society and the musicians to share the profits from the recording. However the audience was so small that the Society was unable to pay the musicians' fees. The musicians were all given NSF checks, and only Parker was able to actually cash his; Gillespie complained that he did not receive his fee "for years and years".

A 2004 re-issue contains the full concert, without the over-dubbing which was added by Charles Mingus on the original recording. The new version was titled "Complete Jazz at Massey Hall"

Jazz at Massey Hall was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1995. It is included in National Public Radio's "Basic Jazz Library". The concert was issued in some territories under the tag "the greatest jazz concert ever".

1. "Perdido" (Juan Tizol, Hans Lengfelder, Ervin M. Drake)

2. "Salt Peanuts" (Dizzy Gillespie, Kenny Clarke)

3. "All the Things You Are" (Jerome Kern, Oscar Hammerstein II)

4. "52nd Street Theme" (Thelonious Monk)

---

5. "Wee (Allen's Alley)" (Denzil Best)

6. "Hot House" (Tadd Dameron)

7. "A Night in Tunisia" (Gillespie, Frank Paparelli)

• Dizzy Gillespie — trumpet

• Charles Mingus — bass

• Charlie Parker — alto sax

• Bud Powell — piano

• Max Roach — drums

After the event, Mingus chose to overdub his barely-audible bass part back in New York; the original version was issued later. The two 10" albums of the Massey Hall concert (one featured the trio of Powell, Mingus and Roach) were among Debut Records' earliest releases. Mingus may have objected to the way the major record companies treated musicians, but Gillespie once commented that he did not receive any royalties "for years and years" for his Massey Hall appearance. The records though, are often regarded as among the finest live jazz recordings.

In the summer he founds the ‘Jazz Workshop’ gathering around him the cream of avant-garde music without making distinctions about the color of people’s skin: Teo Macero, John la Porta, Willie Denis, Eddie Bert, J.J. Johnson, kay Winding & Kenny Clarke. He begins to experiment with these people.

1955-56.

He plays with his group at the Café Bohemia in NY. Some genuine masterpieces as ‘Pithecanthropus erectus’ and ‘Haitian Fight Song’ come in light. In some of his songs social political meanings can be detected, condemning racial persecution and prejudice. Mingus’ arrangements are not fully composed, but just like Ellington, they have lots of space for the soloists to improvise.

Pithecanthropus erectus, 1955

1. "Pithecanthropus Erectus" – 10:36

2. "A Foggy Day" – 7:50 {George Gershwin}

3. "Profile of Jackie" – 3:11

4. "Love Chant" – 14:59

· Charles Mingus – Bass

· Jackie McLean – Alto Saxophone

· J. R. Monterose – Tenor Saxophone

· Mal Waldron – Piano

· Willie Jones – Drums

Pithecanthropus Erectus was Charles Mingus' breakthrough as a leader, the album where he established himself as a composer of boundless imagination and a fresh new voice that, despite his ambitiously modern concepts, was firmly grounded in jazz tradition. Mingus truly discovered himself after mastering the vocabularies of bop and swing, and with Pithecanthropus Erectus he began seeking new ways to increase the evocative power of the art form and challenge his musicians (who here include altoist Jackie McLean and pianist Mal Waldron) to work outside of convention. The title cut is one of his greatest masterpieces: a four-movement tone poem depicting man's evolution from pride and accomplishment to hubris and slavery and finally to ultimate destruction. The piece is held together by a haunting, repeated theme and broken up by frenetic, sound-effect-filled interludes that grow darker as man's spirit sinks lower. It can be a little hard to follow the story line, but the whole thing seethes with a brooding intensity that comes from the soloist's extraordinary focus on the mood, rather than simply flashing their chops. Mingus' playful side surfaces on "A Foggy Day (In San Francisco)," which crams numerous sound effects (all from actual instruments) into a highly visual portrait, complete with honking cars, ringing trolleys, sirens, police whistles, change clinking on the sidewalk, and more. This was the first album where Mingus tailored his arrangements to the personalities of his musicians, teaching the pieces by ear instead of writing everything out. Perhaps that's why Pithecanthropus Erectus resembles paintings in sound -- full of sumptuous tone colors learned through Duke Ellington, but also rich in sonic details that only could have come from an adventurous modernist. And Mingus plays with the sort of raw passion that comes with the first flush of mastery. Still one of his greatest.

[...]

Early 1955, Mingus is involved in a notorious incident while playing a club date billed as a "reunion" with Parker, Powell, and Roach. Powell, who suffered from alcoholism and mental illness (possibly exacerbated by a severe police beating and electroshock treatments), had to be helped from the stage, unable to play or speak coherently. As Powell's incapacitation became apparent, Parker stood in one spot at a microphone, chanting "Bud Powell...Bud Powell..." as if beseeching Powell's return. Allegedly, Parker continued this incantation for several minutes after Powell's departure, to his own amusement and Mingus' exasperation. Mingus took another microphone and announced to the crowd, "Ladies and gentlemen, please don't associate me with any of this. This is not jazz. These are sick people." This was Parker's last public performance; about a week later Parker died after years of substance abuse.

1957.

He contributes to the creation of the sound track for the film ‘Shadows’ by Cassavetes. Release of The Clown.

The Clown, 1957

1. "Haitian Fight Song" - 11:57

2. "Blue Cee" - 7:48

3. "Reincarnation of a Lovebird" - 8:31

4. "The Clown" - 12:29

The following excerpts come from the original liner notes and are statements made by Mingus himself.

On "Haitian Fight Song", Mingus said "[...] It has a folk spirit, the kind of folk music I've always heard anyway.[...] My solo in it it's a deeply concetrated one. I can't play it right unless I'm thinking about prejudice and persecution, and how unfair is it. There's sadness and cries in it, but also determination. And it usually ends with my feeling 'I told them! I hope somebody heard me!'".

"Blue Cee" is a standard blues in two keys, C and Bb, "but that's not noticeable and it ends up in C, basically", he said and continued "I heard some Basie in it and also some church-like feeling".

"Reincarnation of a Lovebird" is a composition dedicated to Bird. "I wouldn't say I set out to write a piece on Bird. [...] Suddenly I realize it was Bird. [...] In one way, the work isn't like him. It's built on long lines and most of his pieces were short lines. But it's my feeling about Bird. I felt like crying when I wrote it."

"The Clown" tells the story of a clown "who tried to please people like most jazz musicians do, but whom nobody liked until he was dead. My version of the story ended with his blowing his brains out with the people laughing and finally being pleased because they thought it was part of the act. I liked the way Jean changed the ending; leaves it more up to the listener."

1959.

This is a very creative year for Mingus, from the album ‘Mingus Ah Um’ with a homage to Charlie Parker (Bird Calls), Duke Ellington (Open Letter To Duke) and to Lester Young, who had recently died (Goodbye Pork Pie Hat). At the end of the 50s, Mingus is a famous personality, loved for his music and feared for his dissoluteness. The relations between him and his colleagues, journalists and producers are almost always turbulent. Sometimes, doing concerts, he urges on his musicians at the top of his voice, flattering them and insulting them, stopping numbers only to begin them again immediately afterwards, almost as if it was a rehearsal and not a payed performance. He takes absolutely no notice of the opinions of the critics and the audiences. This is something new and disconcerting, which creates his legendary image.

Mingus Ah Um, 1959

· "Better Git It in Your Soul" (7:23)

· "Goodbye Pork Pie Hat" (4:46/5:44)

· "Boogie Stop Shuffle" (3:41/5:02)

· "Self-Portrait in Three Colors" (3:10)

· "Open Letter to Duke" (4:56/5:51)

· "Bird Calls" (3:12/6:17)

· "Fables of Faubus" (8:13)

· "Pussy Cat Dues" (6:27/9:14)

· "Jelly Roll" (4:01/6:17)

Charles Mingus' debut for Columbia, Mingus Ah Um is a stunning summation of the bassist's talents and probably the best reference point for beginners. While there's also a strong case for The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady as his best work overall, it lacks Ah Um's immediate accessibility and brilliantly sculpted individual tunes. Mingus' compositions and arrangements were always extremely focused, assimilating individual spontaneity into a firm consistency of mood, and that approach reaches an ultra-tight zenith on Mingus Ah Um. The band includes longtime Mingus stalwarts already well versed in his music, like saxophonists John Handy, Shafi Hadi, and Booker Ervin; trombonists Jimmy Knepper and Willie Dennis; pianist Horace Parlan; and drummer Dannie Richmond. Their razor-sharp performances tie together what may well be Mingus' greatest, most emotionally varied set of compositions. At least three became instant classics, starting with the irrepressible spiritual exuberance of signature tune "Better Get It in Your Soul," taken in a hard-charging 6/8 and punctuated by joyous gospel shouts. "Goodbye Pork Pie Hat" is a slow, graceful elegy for Lester Young, who died not long before the sessions. The sharply contrasting "Fables of Faubus" is a savage mockery of segregationist Arkansas governor Orval Faubus, portrayed musically as a bumbling vaudeville clown (the scathing lyrics, censored by skittish executives, can be heard on Charles Mingus Presents Charles Mingus). The underrated "Boogie Stop Shuffle" is bursting with aggressive swing, and elsewhere there are tributes to Mingus' three most revered influences: "Open Letter to Duke" is a suite of three tunes; "Bird Calls" is inspired by Charlie Parker; and "Jelly Roll" is an idiosyncratic yet affectionate nod to jazz's first great composer, Jelly Roll Morton. It simply isn't possible to single out one Mingus album as definitive, but Mingus Ah Um comes the closest.

...to be continued...

____no5

Free Man

Yeah, difficult person. You can see it in his music as well; the more the years pass, the more it becomes avant garde. The peak is his Epitaph, the longest 'jazz' piece ever. Really strange piece, more classical than jazz if you ask me... I'm sure it'd been way better if he was performing in that one, but, as Mozart, he couldn't complete his 'Requiem' either...

Pithecanthropus Erectus for me. Nice starter. Also there is a compilation of his 55-57 period (Giants of Jazz series) that's also called Pithecanthropus Erectus and could made the ultimate record to start with. Plus the cover is awesome.

Pithecanthropus Erectus for me. Nice starter. Also there is a compilation of his 55-57 period (Giants of Jazz series) that's also called Pithecanthropus Erectus and could made the ultimate record to start with. Plus the cover is awesome.

Forostar

Ancient Mariner

Thanks for the recommendations. There's a lot of Mingus to explore. Right now, I only have this CD:

Charles Mingus & Booker Ervin - The Savoy Recordings. Actually these are two CD's but Mingus doesn't play on the second.

Looking at the tracks, this contains the Mingus album:

Charles Mingus - Jazz Composers Workshop (October 1954 + January 1955)

There's also a bonus track called "O.P." from the album

Charles Mingus with Orchestra (January 1971)

Charles Mingus & Booker Ervin - The Savoy Recordings. Actually these are two CD's but Mingus doesn't play on the second.

Looking at the tracks, this contains the Mingus album:

Charles Mingus - Jazz Composers Workshop (October 1954 + January 1955)

There's also a bonus track called "O.P." from the album

Charles Mingus with Orchestra (January 1971)

____no5

Free Man

I found this article. Interesting read.

The etymology of the word JAZZ

Bob Rigter

[This is an abridged version of Bob Rigter (1991), Light on the Dark Etymology of JAZZ in the Oxford English Dictionary,

in Tieken & Frankis (eds.), Language usage and description, Editions Rodopi, Amsterdam - Atlanta.

ISBN 90-5183-312-1]

This article discusses the entries for the word JAZZ in the 1933 and 1976 supplements to the first edition of the

Oxford English Dictionary (OED), and in the body of the text of the second, 1989, edition. Although, compared to

the 1933 supplement, the 1976 and 1989 entries show a decided improvement in approach and quality, none of

them offers an etymology for the word JAZZ.

In this article, arguments are put forward for a creolized French etymology. The word is derived from

French CHASSE (=hunting).

The 1933 supplement

The entries for JAZZ as a substantive and a verb in the 1933 supplement to the OED are illustrated with quotations

dating from 1918 to 1930. The drift of some of these quotations is derogatory and racist, even though by 1930 the

development of jazz music and jazz culture was already such that the emergence of jazz as America's principal

contribution to world culture was beginning to be discernable. There is no mention of any use of the word JAZZ

before 1918. Clearly, the editors were not aware of, or did not see fit to include, the word JASS on the label of the

first jazz record, which appeared on 7 March 1917, and contained the music of the Original Dixieland Jass Band.

Since one million copies of this record were sold, it must have played an important role in the dissemination of

the word JASS. The 1933 supplement does not provide an etymology of the word JASS or JAZZ.

The 1976 supplement

The entries in the 1976 supplement are illustrated with quotations dating from 1909 to 1974. The number of quotations

is considerably increased, and, with two exceptions dating from 1919, quotations containing the word nigger have

been removed. Also the attitude to jazz, and specifically jazz music, has become less derogatory. Witness, for

example, the suppression of the 1930 quotation from the Observer, in which jazz is opposed to 'real music'.

Note the following entries for JAZZ as a substantive:

a. ... a type of music originating among American Negroes, characterized by its use of improvisation,

syncopated phrasing, a regular or forceful rhythm, often in common time, and a 'swinging' quality ...

b. A piece of jazz music. ...

c. spec. A passage of improvised music in a jazz performance. ...

2. transf. Energy, excitement, 'pep'; restlessness, excitability. ...

3. Meaningless or empty talk, nonsense, rot, 'rubbish'; unnecessary ornamentation; anything unpleasant

or disagreeable. ...

4. slang. Sexual intercourse.

And as a verb:

1. trans. To speed or liven up; to render more colourful, 'modern', or sensational; to excite. ...

b. To play (music, or an instrument) in the style of jazz. Freq. const. up. ...

2. intr. To play jazz; to dance to jazz music. Hence transf., to move in a grotesque or fantastic manner;

to behave wildly...

3. trans. and intr. To have sexual intercourse (with). slang.

The editor of the 1976 supplement has adopted the policy of letting the jazz world do some of its own defining of

what jazz is, by including a number of quotations from jazz musicians such as Jo Jones and Dave Brubeck, jazz

critics such as Leonard Feather and Marshall Stearns, and a music journal such as Melody Maker.

There are also a number of quotations from sources that suggest conceivable origins of the word JAZZ. Many

of these suggestions hint at a black African origin and point to the usage of the word in the Creole dialect in New

Orleans.

No etymology of the word JAZZ is provided.

The second edition of the OED (1989)

The information under JAZZ in the 1976 supplement to the OED is incorporated unaltered in the main body of the

1989 edition. Accordingly, no etymology of the word JAZZ is provided there either.

African slaves and French creolisation

American blacks were imported as slaves from Africa. On the African coast there were French, Dutch, English

and Danish settlements from which the slave trade was carried on. More to the south there were also Portuguese

settlements. The islands Guadeloupe, Martinique and, until 1800, Haïti were French.

In the early nineteenth century, before the first negro republic was founded in Haïti in 1804, French-speaking

white slave-owners fled from Haïti with their slaves to New Orleans in Louisiana. At the time, Louisiana was French.

The year of the Louisiana Purchase, when the Americans bought Louisiana from Napolean, was 1803.

Black slaves were also imported in Louisiana directly from the African coast. A considerable number of the

slaves imported in French-speaking Louisiana, were supplied by French slave traders.

African slaves in Louisiana did not preserve their original African languages. Due to the fact that they had been

captured or bought as individuals from various regional and tribal backgrounds, they developed pidgin languages

in which much of the vocabulary was adopted from the language of their masters. Even today, French continues

to be spoken in certain areas of Louisiana. In view of all this, the conclusion is justified that, in the later nineteenth

century, black speakers in Louisiana would have quite some words of French origin in their vocabulary.

The origin of jazz music

Jazz music originated in New Orleans at the beginning of the twentieth century. Many inhabitants of New Orleans

were Creoles of mixed French and African origin. A number of these Creoles were accomplished musicians, trained

in the European musical tradition. Whatever light-coloured Creoles may have retained of a heritage of African music

was often suppressed due to the demands of cultured behaviour in a society in which Creoles of mixed blood did not

look upon themselves as blacks.

There was a lot of dancing in New Orleans, not only in the Voodoo gatherings of proletarian blacks in Congo

Square, but also at more European picnics, boat-trips, dances and other functions. Musicians were in great demand.

When in 1898 the Spanish-American war ended and military units were disbanded, second-hand shops were full of

clarinets, trumpets, trombones, tubas and drums, which could be bought by even the poorest negroes. For the black

man, becoming a musician was one of the few possible escapes from poverty and heavy physical labour.

Before the birth of jazz music, there were thus two musical traditions in New Orleans. One was white, based on

musical training in the European tradition. The other was black, based on an African aural tradition (see Sidran 1981).

Non-creole proletarian blacks played their instruments by ear. Instead of reading music, they played directly. They

faked and improvised, and used the rhythms and scales they had brought from Africa.

Before the start of Jim Crow legislation, coloured Creoles took up a position in between white and black music, but

closer to the European musical tradition. However, after the Supreme Court's ruling in the Plessy vs. Ferguson case

in 1896, which was to be the start of racial segregation, coloured Creoles were looked upon as black, and began to

suffer the social and economic effects of segregation. One of the results was that they began to mix with black

musicians in the entertainment business.

The mutual influence of Creole musicians and proletarian black musicians led to the birth of jazz. The Creole's

executional sophistication and theoretical knowledge of European music, the black musician's practical creativity

and emotional intensity, and, last but not least, the shared rhythmical roots of blacks and Creoles, gave rise to

the music of one suppressed class of coloured musicians.

Jazz was born. The music was soon imitated and adopted by white musicians. Thus the Original Dixieland Jass

Band, which in 1917 made the first jazz record, was all white. As such, it was presentable in white society and made

a lot of money, which, for a long time to come, could not be said of black jazz.

Rhythm, excitement, sex, dancing and music

Whites looked upon early jazz, and certainly black jazz, as associated with licentious behaviour. Jazz music was

looked upon as whorehouse music. And it is true that early jazz flourished especially in Storyville, the redlight

district of New Orleans. Right from the birth of jazz, there is this close association of rhythm, excitement, sex,

dancing and music that is found in the various meanings of the word JAZZ listed in the OED.

A French etymon for JAZZ

In New Orleans, as also in some coastal areas of Africa and on some islands on the trade route from Africa to

Louisiana, many coloured people spoke a creolised French. If no English origin appears to be available for the

American word JAZZ, a French source would seem quite likely in view of the origin of jazz music in New Orleans,

and in view of its Creole and African roots.

If there is a French etymon for JAZZ, it should satisfy the following criteria:

a. the French word can be aptly used to refer to the sense of accelerating the rhythm of the music without actually

speeding the music up. This seeming acceleration is so crucially characteristic of jazz - and of the African strands

of its origin (see Lafcadio Hearn (1890) p.220) - that a word referring to it would be a suitable label for the music.

b. the French word can be aptly used to the sexual pursuit stylised in the traditional African dance to the African

strands in the origin of this type of rhythmical music. (Again, see Lafcadio Hearn (1890) p.220, where the music

and the dancing in the French West Indies are described. Hearn also refers to a source dating from 1722, in

which the exciting, rhythmical music and overtly sexual motions in dancing to it, are described by a French priest).

c. the French word can be used for sexual intercourse.

d. the French word must be phonetically relatable to JAZZ, or its earlier form JASS.

A French word that meets all these requirements is CHASSE.

CHASSE and JAZZ in French dictionaries

The Grand Larousse de la Langua Française (1971) derives CHASSER from Classical Latin CAPTARE. It provides

two related meanings: 'chercher à prendre' and 'pousser devant soi, obliger à avancer ... faire avancer rapidement'.

Clearly, the first can be related to the sexual connotation, and the second to the rhythmical connotation of the word

JASS as it was used in New Orleans round 1900.

The noun CHASSE is defined (under II.1) as follows: 'Action de poursuivre une personne ou un animal en vu de

s'en emparer.' Among the examples given, are: Faire la chasse au mari; Faire la chasse à une femme.

Le Robert, Dictionnaire de la langue française (1985), agrees with the Grand Larousse almost verbatim, but adds:

'ÊTRE EN CHASSE, en chaleur (se dit de la femelle de certains animaux à l'époque où elle recherche le mâle)'.

Under JAZZ, both dictionaries state that the origin of the word is obscure, and that it used to be written as JASS.

Le Robert, in addition, provides '... un sens dialectal (région de la Nouvelle-Orléans) obscène <<coïter>>'.

Conclusion

I think I have provided the required justification to replace the phrase '[Origin unknown: see quots. for some of the

many suggested derivations. Cf. *JAZZBO]', which we still find in the second edition of the OED, by the phrase

'[creolised F. chasse]' in the next edition.

My conclusion that French CHASSE is the etymon of JAZZ, implies that I do not accept that the proper name

JAZZBO (allegedly an early itinerant Negro player along the Mississippi) may have given rise to the noun and/or

verb JAZZ. This is one of the suggestions found in an entry in the 1976 supplement to the OED. It rather seems

the other way about: JAZZBO might well be a compound of JAZZ and BEAU, both of French origin.

I look upon various additional meanings of JAZZ, such as nonsense, anything unpleasant or disagreeable,

grotesque, riotous and fantastic, as having developed in the wake of negative white reactions to jazz music since

it started spreading in 1917. It is interesting to see that the gradual change in appreciation of jazz music coincides

with the development of less negative meanings, such as lively, sophisticated, unconventional, which are listed in

the 1976, but not in the 1933 supplement to the OED.

References

Dictionaries

A Supplement to the Oxford English Dictionary (1976), ed. by R. W. Burchfield, Vol. II, H - N. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

The Oxford English Dictionary (1989), ed. by J. A. Simpson and E. S. C. Weiner, Oxford: Clarendon Press (2nd ed.)

Grand Larousse de la langue française (1971-8), 6 vols., Paris: Librairie Larousse.

Le Grand Robert de la langue française (1985), 9 vols., Paris: Le Robert (2nd ed.)

Other works

Hearn, Lafcadio (1890) Two Years in the French West Indies, New York/Oxford: Harper & Brothers (repr. 1923).

Sidran, Ben (1981) Black Talk, New York: Da Capo Press.

The etymology of the word JAZZ

Bob Rigter

[This is an abridged version of Bob Rigter (1991), Light on the Dark Etymology of JAZZ in the Oxford English Dictionary,

in Tieken & Frankis (eds.), Language usage and description, Editions Rodopi, Amsterdam - Atlanta.

ISBN 90-5183-312-1]

This article discusses the entries for the word JAZZ in the 1933 and 1976 supplements to the first edition of the

Oxford English Dictionary (OED), and in the body of the text of the second, 1989, edition. Although, compared to

the 1933 supplement, the 1976 and 1989 entries show a decided improvement in approach and quality, none of

them offers an etymology for the word JAZZ.

In this article, arguments are put forward for a creolized French etymology. The word is derived from

French CHASSE (=hunting).

The 1933 supplement

The entries for JAZZ as a substantive and a verb in the 1933 supplement to the OED are illustrated with quotations

dating from 1918 to 1930. The drift of some of these quotations is derogatory and racist, even though by 1930 the

development of jazz music and jazz culture was already such that the emergence of jazz as America's principal

contribution to world culture was beginning to be discernable. There is no mention of any use of the word JAZZ

before 1918. Clearly, the editors were not aware of, or did not see fit to include, the word JASS on the label of the

first jazz record, which appeared on 7 March 1917, and contained the music of the Original Dixieland Jass Band.

Since one million copies of this record were sold, it must have played an important role in the dissemination of

the word JASS. The 1933 supplement does not provide an etymology of the word JASS or JAZZ.

The 1976 supplement

The entries in the 1976 supplement are illustrated with quotations dating from 1909 to 1974. The number of quotations

is considerably increased, and, with two exceptions dating from 1919, quotations containing the word nigger have

been removed. Also the attitude to jazz, and specifically jazz music, has become less derogatory. Witness, for

example, the suppression of the 1930 quotation from the Observer, in which jazz is opposed to 'real music'.

Note the following entries for JAZZ as a substantive:

a. ... a type of music originating among American Negroes, characterized by its use of improvisation,

syncopated phrasing, a regular or forceful rhythm, often in common time, and a 'swinging' quality ...

b. A piece of jazz music. ...

c. spec. A passage of improvised music in a jazz performance. ...

2. transf. Energy, excitement, 'pep'; restlessness, excitability. ...

3. Meaningless or empty talk, nonsense, rot, 'rubbish'; unnecessary ornamentation; anything unpleasant

or disagreeable. ...

4. slang. Sexual intercourse.

And as a verb:

1. trans. To speed or liven up; to render more colourful, 'modern', or sensational; to excite. ...

b. To play (music, or an instrument) in the style of jazz. Freq. const. up. ...

2. intr. To play jazz; to dance to jazz music. Hence transf., to move in a grotesque or fantastic manner;

to behave wildly...

3. trans. and intr. To have sexual intercourse (with). slang.

The editor of the 1976 supplement has adopted the policy of letting the jazz world do some of its own defining of

what jazz is, by including a number of quotations from jazz musicians such as Jo Jones and Dave Brubeck, jazz

critics such as Leonard Feather and Marshall Stearns, and a music journal such as Melody Maker.

There are also a number of quotations from sources that suggest conceivable origins of the word JAZZ. Many

of these suggestions hint at a black African origin and point to the usage of the word in the Creole dialect in New

Orleans.

No etymology of the word JAZZ is provided.

The second edition of the OED (1989)

The information under JAZZ in the 1976 supplement to the OED is incorporated unaltered in the main body of the

1989 edition. Accordingly, no etymology of the word JAZZ is provided there either.

African slaves and French creolisation

American blacks were imported as slaves from Africa. On the African coast there were French, Dutch, English

and Danish settlements from which the slave trade was carried on. More to the south there were also Portuguese

settlements. The islands Guadeloupe, Martinique and, until 1800, Haïti were French.

In the early nineteenth century, before the first negro republic was founded in Haïti in 1804, French-speaking

white slave-owners fled from Haïti with their slaves to New Orleans in Louisiana. At the time, Louisiana was French.

The year of the Louisiana Purchase, when the Americans bought Louisiana from Napolean, was 1803.

Black slaves were also imported in Louisiana directly from the African coast. A considerable number of the

slaves imported in French-speaking Louisiana, were supplied by French slave traders.

African slaves in Louisiana did not preserve their original African languages. Due to the fact that they had been

captured or bought as individuals from various regional and tribal backgrounds, they developed pidgin languages

in which much of the vocabulary was adopted from the language of their masters. Even today, French continues

to be spoken in certain areas of Louisiana. In view of all this, the conclusion is justified that, in the later nineteenth

century, black speakers in Louisiana would have quite some words of French origin in their vocabulary.

The origin of jazz music

Jazz music originated in New Orleans at the beginning of the twentieth century. Many inhabitants of New Orleans

were Creoles of mixed French and African origin. A number of these Creoles were accomplished musicians, trained

in the European musical tradition. Whatever light-coloured Creoles may have retained of a heritage of African music

was often suppressed due to the demands of cultured behaviour in a society in which Creoles of mixed blood did not

look upon themselves as blacks.

There was a lot of dancing in New Orleans, not only in the Voodoo gatherings of proletarian blacks in Congo

Square, but also at more European picnics, boat-trips, dances and other functions. Musicians were in great demand.

When in 1898 the Spanish-American war ended and military units were disbanded, second-hand shops were full of

clarinets, trumpets, trombones, tubas and drums, which could be bought by even the poorest negroes. For the black

man, becoming a musician was one of the few possible escapes from poverty and heavy physical labour.

Before the birth of jazz music, there were thus two musical traditions in New Orleans. One was white, based on

musical training in the European tradition. The other was black, based on an African aural tradition (see Sidran 1981).

Non-creole proletarian blacks played their instruments by ear. Instead of reading music, they played directly. They

faked and improvised, and used the rhythms and scales they had brought from Africa.

Before the start of Jim Crow legislation, coloured Creoles took up a position in between white and black music, but

closer to the European musical tradition. However, after the Supreme Court's ruling in the Plessy vs. Ferguson case

in 1896, which was to be the start of racial segregation, coloured Creoles were looked upon as black, and began to

suffer the social and economic effects of segregation. One of the results was that they began to mix with black

musicians in the entertainment business.

The mutual influence of Creole musicians and proletarian black musicians led to the birth of jazz. The Creole's

executional sophistication and theoretical knowledge of European music, the black musician's practical creativity

and emotional intensity, and, last but not least, the shared rhythmical roots of blacks and Creoles, gave rise to

the music of one suppressed class of coloured musicians.

Jazz was born. The music was soon imitated and adopted by white musicians. Thus the Original Dixieland Jass

Band, which in 1917 made the first jazz record, was all white. As such, it was presentable in white society and made

a lot of money, which, for a long time to come, could not be said of black jazz.

Rhythm, excitement, sex, dancing and music

Whites looked upon early jazz, and certainly black jazz, as associated with licentious behaviour. Jazz music was

looked upon as whorehouse music. And it is true that early jazz flourished especially in Storyville, the redlight

district of New Orleans. Right from the birth of jazz, there is this close association of rhythm, excitement, sex,

dancing and music that is found in the various meanings of the word JAZZ listed in the OED.

A French etymon for JAZZ

In New Orleans, as also in some coastal areas of Africa and on some islands on the trade route from Africa to

Louisiana, many coloured people spoke a creolised French. If no English origin appears to be available for the

American word JAZZ, a French source would seem quite likely in view of the origin of jazz music in New Orleans,

and in view of its Creole and African roots.

If there is a French etymon for JAZZ, it should satisfy the following criteria:

a. the French word can be aptly used to refer to the sense of accelerating the rhythm of the music without actually

speeding the music up. This seeming acceleration is so crucially characteristic of jazz - and of the African strands

of its origin (see Lafcadio Hearn (1890) p.220) - that a word referring to it would be a suitable label for the music.

b. the French word can be aptly used to the sexual pursuit stylised in the traditional African dance to the African

strands in the origin of this type of rhythmical music. (Again, see Lafcadio Hearn (1890) p.220, where the music

and the dancing in the French West Indies are described. Hearn also refers to a source dating from 1722, in

which the exciting, rhythmical music and overtly sexual motions in dancing to it, are described by a French priest).

c. the French word can be used for sexual intercourse.

d. the French word must be phonetically relatable to JAZZ, or its earlier form JASS.

A French word that meets all these requirements is CHASSE.

CHASSE and JAZZ in French dictionaries

The Grand Larousse de la Langua Française (1971) derives CHASSER from Classical Latin CAPTARE. It provides

two related meanings: 'chercher à prendre' and 'pousser devant soi, obliger à avancer ... faire avancer rapidement'.

Clearly, the first can be related to the sexual connotation, and the second to the rhythmical connotation of the word

JASS as it was used in New Orleans round 1900.

The noun CHASSE is defined (under II.1) as follows: 'Action de poursuivre une personne ou un animal en vu de

s'en emparer.' Among the examples given, are: Faire la chasse au mari; Faire la chasse à une femme.

Le Robert, Dictionnaire de la langue française (1985), agrees with the Grand Larousse almost verbatim, but adds:

'ÊTRE EN CHASSE, en chaleur (se dit de la femelle de certains animaux à l'époque où elle recherche le mâle)'.

Under JAZZ, both dictionaries state that the origin of the word is obscure, and that it used to be written as JASS.

Le Robert, in addition, provides '... un sens dialectal (région de la Nouvelle-Orléans) obscène <<coïter>>'.

Conclusion

I think I have provided the required justification to replace the phrase '[Origin unknown: see quots. for some of the

many suggested derivations. Cf. *JAZZBO]', which we still find in the second edition of the OED, by the phrase

'[creolised F. chasse]' in the next edition.

My conclusion that French CHASSE is the etymon of JAZZ, implies that I do not accept that the proper name

JAZZBO (allegedly an early itinerant Negro player along the Mississippi) may have given rise to the noun and/or

verb JAZZ. This is one of the suggestions found in an entry in the 1976 supplement to the OED. It rather seems

the other way about: JAZZBO might well be a compound of JAZZ and BEAU, both of French origin.

I look upon various additional meanings of JAZZ, such as nonsense, anything unpleasant or disagreeable,

grotesque, riotous and fantastic, as having developed in the wake of negative white reactions to jazz music since

it started spreading in 1917. It is interesting to see that the gradual change in appreciation of jazz music coincides

with the development of less negative meanings, such as lively, sophisticated, unconventional, which are listed in

the 1976, but not in the 1933 supplement to the OED.

References

Dictionaries

A Supplement to the Oxford English Dictionary (1976), ed. by R. W. Burchfield, Vol. II, H - N. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

The Oxford English Dictionary (1989), ed. by J. A. Simpson and E. S. C. Weiner, Oxford: Clarendon Press (2nd ed.)

Grand Larousse de la langue française (1971-8), 6 vols., Paris: Librairie Larousse.

Le Grand Robert de la langue française (1985), 9 vols., Paris: Le Robert (2nd ed.)

Other works

Hearn, Lafcadio (1890) Two Years in the French West Indies, New York/Oxford: Harper & Brothers (repr. 1923).

Sidran, Ben (1981) Black Talk, New York: Da Capo Press.

Holy Moses. 5, you've been busy.

I have one Mingus album - the legendary Black Saint And The Sinner Lady. I've heard Mingus Ah Um years ago.

I've also heard the Joni Mitchell album Foro got, just as many years ago. I listened because it has Jaco Pastorius on bass, one of the most innovative and breathtaking musicians ever. Not just bassist - musician.

Sadly, I cannot report what I thought of those albums. I know I heard them, my roommate (a bassist like me) played them for me and insisted I get educated. However, I was smoking dope for breakfast back in those days. THC + 21 years = lots of memory holes.

Mingus is indeed difficult music. You must meet him on his terms. It's not impossible; he wasn't avant-garde, just very inventive. It's not as difficult as Coltrane's avant-garde albums like Sun King.

I have one Mingus album - the legendary Black Saint And The Sinner Lady. I've heard Mingus Ah Um years ago.

I've also heard the Joni Mitchell album Foro got, just as many years ago. I listened because it has Jaco Pastorius on bass, one of the most innovative and breathtaking musicians ever. Not just bassist - musician.

Sadly, I cannot report what I thought of those albums. I know I heard them, my roommate (a bassist like me) played them for me and insisted I get educated. However, I was smoking dope for breakfast back in those days. THC + 21 years = lots of memory holes.

Mingus is indeed difficult music. You must meet him on his terms. It's not impossible; he wasn't avant-garde, just very inventive. It's not as difficult as Coltrane's avant-garde albums like Sun King.

Forostar

Ancient Mariner

You mean Sun Ship? I really like that album. Some really long songs, but I like the way the songs shift. There's also some slower tempo's on it. And a capella bass solo as well, if I remember well.

Do you know Ascension or Meditations? That's more difficult stuff I think. Some wild stuff, especially the latter. Pretty frantic, with lots of short, fast repetitions in the solos. Very intense and sometimes hard to bear. Also Interstellar Space is quite wild. Coltrane duels with a drummer, both it's almost like they are not paying attention to each other. I guess they do, because they fire up each others intensity, but it's not like they try to adapt to eachother rhythmically.

I was planning to contribute to this topic last week, but it didn't happen. Hopefully more luck this week.

Up next, I'd like to do a bit on Art Blakey.

Do you know Ascension or Meditations? That's more difficult stuff I think. Some wild stuff, especially the latter. Pretty frantic, with lots of short, fast repetitions in the solos. Very intense and sometimes hard to bear. Also Interstellar Space is quite wild. Coltrane duels with a drummer, both it's almost like they are not paying attention to each other. I guess they do, because they fire up each others intensity, but it's not like they try to adapt to eachother rhythmically.

I was planning to contribute to this topic last week, but it didn't happen. Hopefully more luck this week.

Up next, I'd like to do a bit on Art Blakey.

Yes, I did mean Sun Ship, thanks.

Forostar

Ancient Mariner

I have always been into drums. I’ve drummed myself, and drums really led me to many forms of music. Jazz was no exception. Drums have a very special role in jazz. Rhythm has a very special role in jazz.

One of the drummers I admire is Art Blakey. He said (something in the vein of):

“A jazz band is as strong as its drummer”.

Since I am heavily into drums and rhythms I find it hard to disagree with that.

At the moment of writing I own 14 Art Blakey albums.

Some of my personal favourites:

Mosaic (recorded on October 2, 1960)

Line-up:

Freddie Hubbard – trumpet

Curtis Fuller – trombone

Wayne Shorter – tenor sax

Cedar Walton – piano

Jymie Merritt – bass

Art Blakey – drums

This album I love for its quality songwriting, and soloing. The title track, written by Walton is a fantastic piece of hardbob: Mosaic

Art could drive his members like no one. His ride cymbal is like a knife slicing hot butter. All other songs are strong too. I dig the harmonies and the firebreathing Shorter solos.

The second album I’ll choose is one of the live albums.

At the Café Bohemia (released on CD in two volumes) (recorded on November 23, 1955)

This album features Kenny Dorham (trumpet) and Hank Mobley (tenor sax) who proves to be a gifted songwriter. I actually didn’t think his solo album songs were that super, but everything he touches for the Messengers is golden. Check out Avila & Tequila. Lovely piano motive!

Another famous live album, also two volumes, is A Night at Birdland (February 21, 1954), which features Clifford Brown on trumpet and pianist Horace Silver –with his funky style- who was very important for the development of the sound of the Jazz Messengers.

.jpg?ts=1277497464)

Check out Split Kick (note the drum solo @ 8.00 -> you gotta love that tom work).

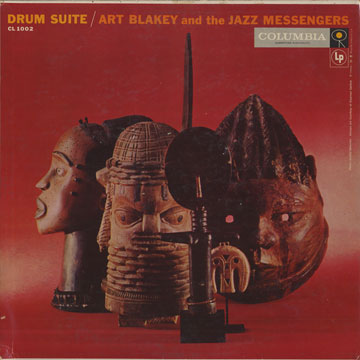

The fourth album I’d like to recommend is something totally different. Blakey was very famous for his albums with the Messengers but we shouldn’t overlook his other work. He made a handful of albums with different instruments. Check the instruments and you’ll see:

Drum Suite (recorded on February 22, 1957)

(the cover mentions Jazz Messengers but the main songs are by a non typical line-up)

Ray Bryant – piano

Oscar Pettiford – bass, cello

Art Blakey – drums

Jo Jones – drums

Specs Wright – drums, tympani, gong, vocals

Candido Camero – congas, percussion, vocals, bass (on one track)

Sabu Martinez – bongos, congas, percussion, vocals

Yes indeed, a “percussion ensemble”! No horns.

Unfortunately no audio on YouTube (Columbia records is strict I guess ) but I tell you:

) but I tell you:

This is really swinging stuff. I love the way some of those songs are built. Really nice how the drummers and percussionists join eachother and give room to eachother. The booklet of the 2005 CD re-release features a very nice explanation by Kenny Washington (also a drummer).

I still have many albums to obtain. My current wishlist is as follows:

Drums Around The Corner 1959

Jazz Messengers (live in Geneva) 1960

Three Blind Mice, Vol. 1 1962

Three Blind Mice, Vol. 2 1961/1962

African Beat, The 1962

Buhaina’s Delight 1962

Indestructable 1964

Hold On, I’m Coming 1966

Anthenagin 1973

But when I made this, I didn’t focus that much on his fifties work. Now it seems I like his older stuff at least as much!

Perhaps the best thing of Blakey was that –with the Messengers- he always surrounded himself with young talented players, and most of them became big leaders themselves.

Apart from the Messengers, and his leader albums, Blakey played with some very famous jazz figures. One of them was the high priest of modern jazz, Thelonious Monk. I really like Monk's Trio album for Prestige, with Blakey and Roach on drums.

The following is from wiki:

By the late forties and early fifties, Blakey was backing musicians such as Miles Davis, Bud Powell and Thelonious Monk — he is often considered to have been Monk's most empathetic drummer, and he played on both Monk's first recording session as a leader (for Blue Note Records in 1947) and his final one (in London in 1971), as well as many in between.

Up to the 1960s Blakey also recorded as a sideman with many other musicians: Jimmy Smith, Herbie Nichols, Cannonball Adderley, Grant Green, and Jazz Messengers graduates Lee Morgan and Hank Mobley, amongst many others. However, after the mid-1960s he mostly concentrated on his own work as a leader.

One of the drummers I admire is Art Blakey. He said (something in the vein of):

“A jazz band is as strong as its drummer”.

Since I am heavily into drums and rhythms I find it hard to disagree with that.

At the moment of writing I own 14 Art Blakey albums.

Some of my personal favourites:

Mosaic (recorded on October 2, 1960)

Line-up:

Freddie Hubbard – trumpet

Curtis Fuller – trombone

Wayne Shorter – tenor sax

Cedar Walton – piano

Jymie Merritt – bass

Art Blakey – drums

This album I love for its quality songwriting, and soloing. The title track, written by Walton is a fantastic piece of hardbob: Mosaic

Art could drive his members like no one. His ride cymbal is like a knife slicing hot butter. All other songs are strong too. I dig the harmonies and the firebreathing Shorter solos.

The second album I’ll choose is one of the live albums.

At the Café Bohemia (released on CD in two volumes) (recorded on November 23, 1955)

This album features Kenny Dorham (trumpet) and Hank Mobley (tenor sax) who proves to be a gifted songwriter. I actually didn’t think his solo album songs were that super, but everything he touches for the Messengers is golden. Check out Avila & Tequila. Lovely piano motive!

Another famous live album, also two volumes, is A Night at Birdland (February 21, 1954), which features Clifford Brown on trumpet and pianist Horace Silver –with his funky style- who was very important for the development of the sound of the Jazz Messengers.

.jpg?ts=1277497464)

Check out Split Kick (note the drum solo @ 8.00 -> you gotta love that tom work).

The fourth album I’d like to recommend is something totally different. Blakey was very famous for his albums with the Messengers but we shouldn’t overlook his other work. He made a handful of albums with different instruments. Check the instruments and you’ll see:

Drum Suite (recorded on February 22, 1957)

(the cover mentions Jazz Messengers but the main songs are by a non typical line-up)

Ray Bryant – piano

Oscar Pettiford – bass, cello

Art Blakey – drums

Jo Jones – drums

Specs Wright – drums, tympani, gong, vocals

Candido Camero – congas, percussion, vocals, bass (on one track)

Sabu Martinez – bongos, congas, percussion, vocals

Yes indeed, a “percussion ensemble”! No horns.

Unfortunately no audio on YouTube (Columbia records is strict I guess

) but I tell you:

) but I tell you:This is really swinging stuff. I love the way some of those songs are built. Really nice how the drummers and percussionists join eachother and give room to eachother. The booklet of the 2005 CD re-release features a very nice explanation by Kenny Washington (also a drummer).

I still have many albums to obtain. My current wishlist is as follows:

Drums Around The Corner 1959

Jazz Messengers (live in Geneva) 1960

Three Blind Mice, Vol. 1 1962

Three Blind Mice, Vol. 2 1961/1962

African Beat, The 1962

Buhaina’s Delight 1962

Indestructable 1964

Hold On, I’m Coming 1966

Anthenagin 1973